Models 1 and 2

Source: Argyris and Schon: elements of their models

Models 1 and 2

We mentioned earlier a number of possible governing values, including “maximise winning and minimise losing” and “minimise expressing negative feelings”. Some of these governing values tend to cluster together to form what might be called world views.

Argyris and Schön identified two such clusters. They term them Model 1 and Model 2. 5 Model 1 might be described as a competitive and defensive stance towards the world. Model 2 is more collaborative and less defensive.

In more detail, Argyris describes the governing values of Model 1 as follows [1982, p.86]…

“Achieve the purposes as the actor perceives themMaximise winning and minimise losing

Minimise eliciting negative feelings

Be rational and minimise emotionality”

This produces adversarial and defensive action strategies, poor relationships, and poor learning.

On the other hand, the governing values for Model 2 are [1982, p.102]…

“Valid informationFree and informed choice

Internal commitment to the choice and constant monitoring of the implementation”

The action strategies here, less defensive and more collaborative, are also more conducive to effective relationships and learning.

In his work, Argyris has found that it is not unusual for people to advocate Model 2 values and to think they express them in action. That is, their espoused theories are Model 2. Our own view is that in our frequently adversarial culture people often show a mix of Models 1 and 2 in their espoused theories. To the extent that they think the situation allows them, however, many are willing to move as far towards Model 2 as possible. We agree with Argyris that their actions, especially when under threat, show the defensiveness of Model 1.

In his books and papers Argyris gives many verbatim accounts of the work he does. It is obvious from this material that people do often think they are acting out of Model 2 values. Whenever there is a potential for threat in the situation, however, they are likely to behave in the defensive ways which imply Model 1 values.

For example, he often asks them to give feedback to each other on their behaviour, or to role play the giving of feedback in case-study situations. Their feedback is given in an attacking way, or so carefully and tentatively that the information is “fuzzy” &endash; he describes the latter as “easing in”. In the terms that we have used in other documentation (for example, Dick, 1986), they use the Model 1 actions of blame and criticism and demand, or talk in generalisations. They do not actually use the specific and non-defensive communication which they advocate to others and believe they are trying to use.

We have already talked about the way in which governing values are expressed in action strategies which in turn have consequences. We will shortly describe the way in which Model 1 values produces single-loop learning. Following Argyris, one might summarise the results as follows …

|

values |

strategy |

|

|

|

goals |

|

|

|

|

|

the task |

|

learning |

|

|

protect self |

norms |

|

|

|

protect others |

|

learning |

Compare this summary to the conventional beliefs about proper behaviour in many organisations and social systems. You will probably agree with Argyris that most of our social systems are Model 1 systems.

We address some of the reasons for this in our monograph Politics, conflict and culture, especially the discussion of the social change model we call the second watershed.

To summarise the main features of the second watershed model … The wider culture in the developed world is in many respects autocratic, and rational in the narrow sense of the term. Stable environments allow bureaucratic and controlled organisations to operate profitably within this culture. Substantial change (for example through double-loop learning) happens rarely and slowly. When environmental change is also slow, this may not be a serious problem.

An important feature of such systems is that there is a “right behaviour” for any situation. People are taught fixed solutions to cope with both their tasks and their relationships. The social rules they follow are detailed, specific, and often held as beliefs without reason.

In many organisations people are not encouraged to take responsibility for their actions. Superiors are responsible for subordinates’ actions. Subordinates follow orders, as revealed by a reliance upon procedures and rules.

In one organisation where one of us was helping with cultural change there were over 70 procedure manuals of one form or another. People previously were expected to follow them carefully in their work. This organisation was trying to change into a more responsive system. As part of a change workshop a senior manager informed the rank-and-file participants that in future, procedure manuals were to be merely guides to action &endash; the employees were expected to work out for themselves what should be done, and to do it. The astonishment on participants’ faces signalled this as a virtual revolution.

It is hardly surprising that in such a system the reasons behind behaviour are often lost in history. It is also to be expected that people assume that other people “know the rules”, and know what they mean. Any perceived departure from the rules is then likely to be labelled disobedience even if it is ignorance or a differing interpretation.

At times such as this, when organisations face constantly changing environments, the difficulties multiply. The tacit rules are yesterday’s rules. The more rapid the environmental changes, the more likely that the rules are inappropriate and the interpretations of them varied.

Organisations (and other social systems) display a number of other important features which add to this effect…

Power is one. When there are power differences between people, it is often tempting to “solve” problems (or at least dispose of them) by fiat rather than understanding.Specialisation is another. People pursue the goals of their own position or section or branch, and may thus lose sight of the overall goals. This makes for competition rather than collaboration between person and person and between section and section.

Designing organisations around jobs rather than around people is a third. People are expected to leave at home the more individual aspects of themselves, including their thoughts and feelings. A false rationality results.

The result is that people are again denied the information they need to understand what is happening. Lacking this, they use competitive and adversarial methods if personal or sectional well-being is at risk. In many organisations and other social systems you don’t get better resources by being honest. You do better by telling selective truths or, if you can get away with it, plausible lies.

Notice, too, that almost all of our most influential social institutions are adversarial in nature. Our courts of law, our political systems, our meeting procedures, our examination procedures, our industrial relations systems &endash; these and more are adversarial in important respects. People are encouraged to present information selectively. Those who are honest risk being treated as deviants.

To someone willing to observe closely and put aside preconceptions, our Model 1 social rules are demonstrated often.

Compare the description above to a Model 2 system. Model 2 is clearly a very different theory of action. It requires that people operate more consensually, with more openness about beliefs and feelings. It goes counter to many of the implicit rules we follow. This, we presume, is one of the reasons why cultural change (or personal change for that matter) is so often difficult.

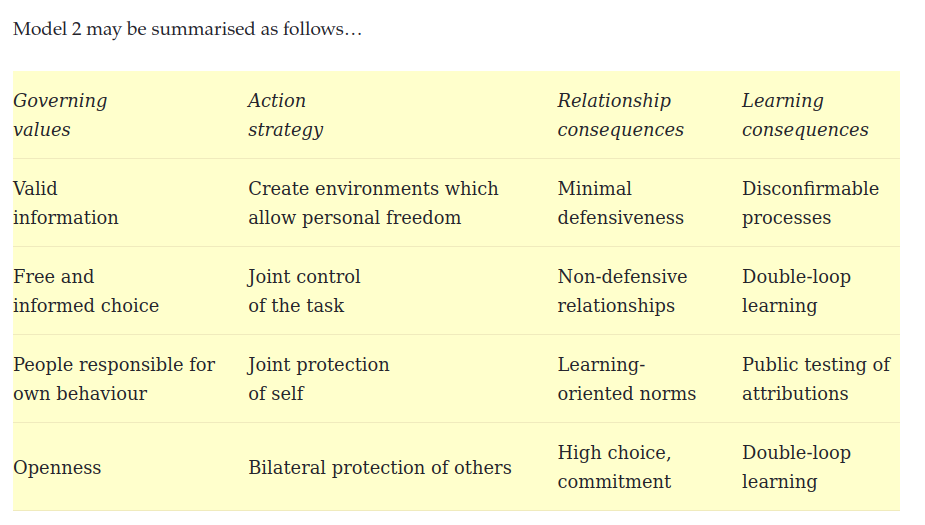

Model 2 may be summarised as follows…

| Governing values |

Action strategy |

Relationship consequences | Learning consequences |

| Valid information |

Create environments which allow personal freedom | Minimal defensiveness | Disconfirmable processes |

| Free and informed choice |

Joint control of the task |

Non-defensive relationships | Double-loop learning |

| People responsible for own behaviour | Joint protection of self |

Learning-oriented norms | Public testing of attributions |

| Openness | Bilateral protection of others | High choice, commitment | Double-loop learning |

In other words, Model 1 processes encourage only superficial learning. The underlying assumptions are treated as fixed. Model 2 processes allow more substantial learning and change by allowing values and assumptions to be tested.